the intelligence of joy

why joy is a form of wisdom - and our best defence against clever despair

Before we dive in, a soft thank you. Since my last essay, The Key to Love is Understanding, something unexpected happened: it became my most-read piece yet, and with it came new eyes, new minds, new hearts. If you’re one of them, hi. I’m so glad you’re here and it means more than you know. This little patch of velvet noise feels richer for your presence. Now onto today’s piece:

the quiet heaviness of perception

In recent years, I’ve noticed a quiet heaviness that seems to settle around certain kinds of minds - sensitive, searching, unusually attuned to the undercurrents of complexity. Perhaps you know this feeling too. Many of us who try to think deeply and feel intensely find ourselves carrying it.

This strikes me as something rather intimate, like a private burden. As if the ongoing act of perception, the constant scanning, sensing, seeing, has slowly worn us down, as if we no longer quite remember how to access wonder.

We may speak fluently about suffering. We try to see the world in systems, in probabilities, in failure modes. We try to understand how things break, and why they tend to stay that way. While we may not say it aloud, there’s often a quiet sense that our perception has become a kind of weight, making everything more legible, but also heavier.

There’s a common trope that the more intelligent someone is, the more likely they are to be unhappy. From what I can tell, the actual research on this is mixed. But it does seem that people who are highly attuned - whether intellectually, emotionally, or existentially - can find it harder to stay connected to joy. Constant vigilance dulls one’s capacity for awe.

I don’t think we’re wrong in what we perceive. The problem is that seeing, when it becomes relentless, can exhaust the soul. The habit of constant analysis - of scanning for collapse and interpreting signals of doom - can gradually erode our ability to be surprised, or moved, or hopeful. It sharpens the mind but slowly desaturates the spirit.

Sometimes, when we’ve trained ourselves to see clearly, we forget how to marvel. We can map every possible outcome, but stop believing in even the smallest miracles.

This troubles me, because I believe the future quite literally depends on our capacity to care, and our willingness to keep believing in futures worth building.

the emotional infrastructure of tomorrow

The people I’m describing are not just thinkers in the abstract. They are builders and shapers, architects of systems and stories, decision-makers whose inner states inevitably ripple outward into the world. Their beliefs don’t stay contained in private notebooks or late-night thoughts, but show up in product roadmaps, in research agendas, in the design of platforms and policies. The way they see the world becomes the scaffolding the rest of us inhabit.

This is why everyone’s inner lives matters beyond a therapeutic sense. Our inner lives are relevant structurally, culturally, historically. Our moods become design constraints. Our default stance toward the world, whether one of numbness or wonder, despair or possibility, gets embedded in the technologies they build and the incentives we set. It colours the metaphors we reach for and shapes the dreams we think it’s acceptable to have.

So when we stop believing in the possibility of renewal, or start treating hope as childish or embarrassing, that loss doesn’t stay personal, but rather becomes ambient. It becomes policy, code, and culture. I have a growing conviction that our capacity for joy, for softness, for belief, may be one of the most critical and least discussed variables shaping the decades ahead.

Because what happens when those imagining the future, which is all of us to an extent, no longer feel that it’s worth imagining? What kind of world will we end up with then?

the seduction of clever despair

Cynicism has become a kind of shorthand for intelligence in the modern age. It wears the costume of insight, sharp, ironic, detached. It rarely commits to anything except critique. It’s the posture of someone who has seen enough to know better, and now keeps their distance from anything that might require emotional investment. Hope, in this frame, is framed as naïveté. Belief is treated as aesthetic weakness.

Yet, I think beneath this knowing smirk is often something more fragile: disappointment, fatigue, a longing that curdled into mockery.

Of course, cynicism is not without function. Sometimes it is a protective shell, an immune response to too many losses, too many broken promises. But cleverness alone does not nourish the world. It cannot carry meaning, only interrogate it. And it often becomes a trap: a place to stand that feels safe because it requires no movement, no action, no risk of hope.

The danger, I think is in mistaking detachment for maturity. Wisdom involves discernment and responsibility, seeing the world clearly, without the abdication of care.

the necessity of optimism

Of course, we must be lucid about the realities of our time. I am not advocating for delusion, nor for any softening of the hard edges that define this moment. To live attentively now is to be aware, often painfully so, of the deep fractures that shape this world. The ecological crisis is not a poetic metaphor. Structural injustice is not an abstraction. The threats we face are real, measurable, and immediate.

But clarity need not preclude belief. In fact, belief forged in full awareness is stronger than any denial.

What I am advocating for is a form of optimism that begins after despair, the kind that emerges from intimate knowledge of what is at stake, not avoidance. This optimism is rigorous, earned and necessary, far beyond passive, frivolous or blind.

Kevin Kelly, co-founder of Wired, calls optimism the belief that problems are solvable1. It’s a discipline of attention toward what might still be possible. This belief also has consequences. Cynicism might feel smarter, but it leads to stagnation. Real, difficult optimism is what gets people to try.

When the people trying are the ones shaping our collective future, their beliefs can matter even more. It’s not uncommon to hear, in hushed tones, that Elon Musk is profoundly unhappy. I don’t know how true that is, but I do know if it is true, it matters. Because the people with the greatest influence over our collective tools and timelines do not build in a vacuum. They build within, and through, their own psychological weather systems. Their moods become ambient and their shadows leak into the infrastructure.

When someone like Musk loses faith in humanity, or in the softness of things, that loss is far from personal. It becomes embedded in code, in product culture, in ambition itself. Emotional worlds become material ones, especially when scaled through capital and influence. But even outside the spotlight, the same truth applies: what we believe and feel shapes what we build.

on the intelligence of receptivity

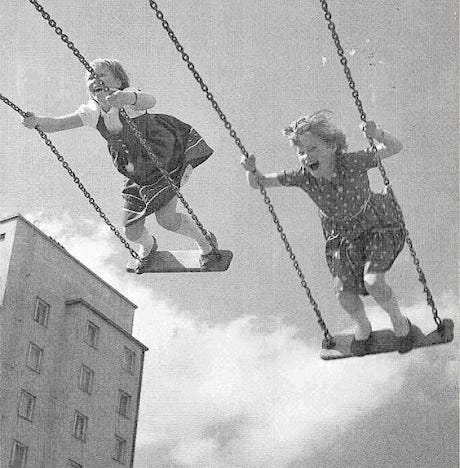

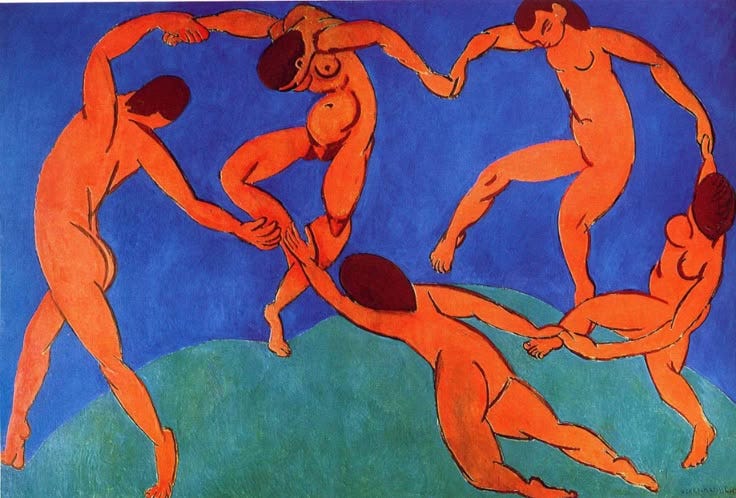

Many people trained in analysis and prediction find it easy to scrutinise, to find the flaw, to stay two steps ahead of disappointment. But these same habits often make it difficult to simply receive beauty, affection, awe, joy. In a world that asks for control at every turn, I think the capacity to be touched, to be moved without precondition, could be a survival skill and a route back to aliveness.

Joy requires a kind of openness that runs counter to our training. It can only be allowed, refusing to be dissected. To receive is to allow experience to arrive unfiltered, without needing it to justify itself first. Receptivity is a kind of intelligence that listens and welcomes, before dominating and interrogating.

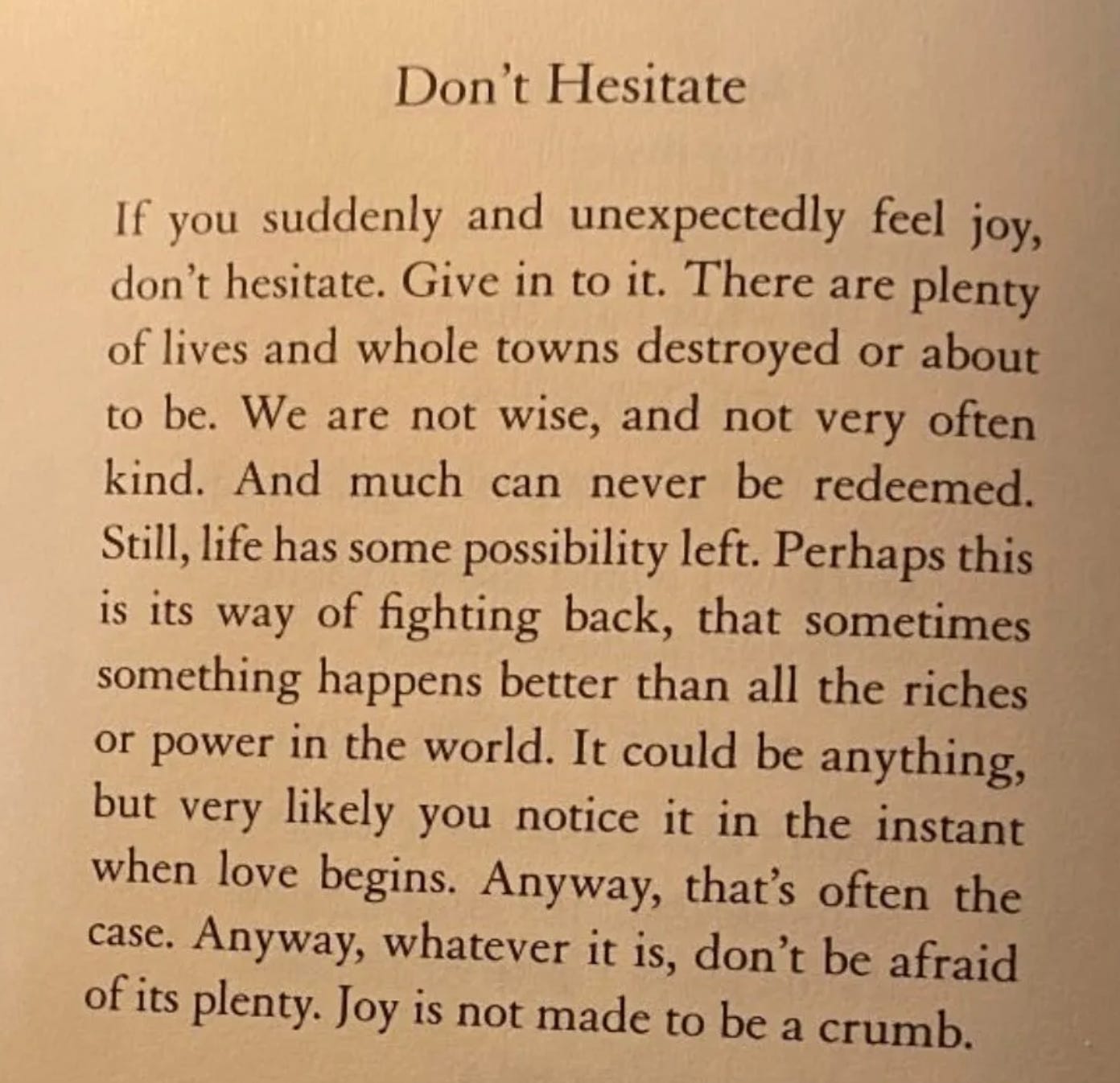

When it arrives, joy deserves reverence. It is not a crumb, nor necessarily an escape or symptom of ignorance. It is a spark, perhaps the very thing that keeps us from going numb, a refusal to collapse into cynicism. As Mary Oliver, a prophet of joy, says in one of my favourite poems ‘Don’t Hesitate’:

This poem, to me, is about the sacredness of noticing. It reminds me that the things which give life its texture - beauty, connection, wonder - do not need to justify themselves by solving anything. They are worth protecting simply because they exist.

let us stay open to wonder

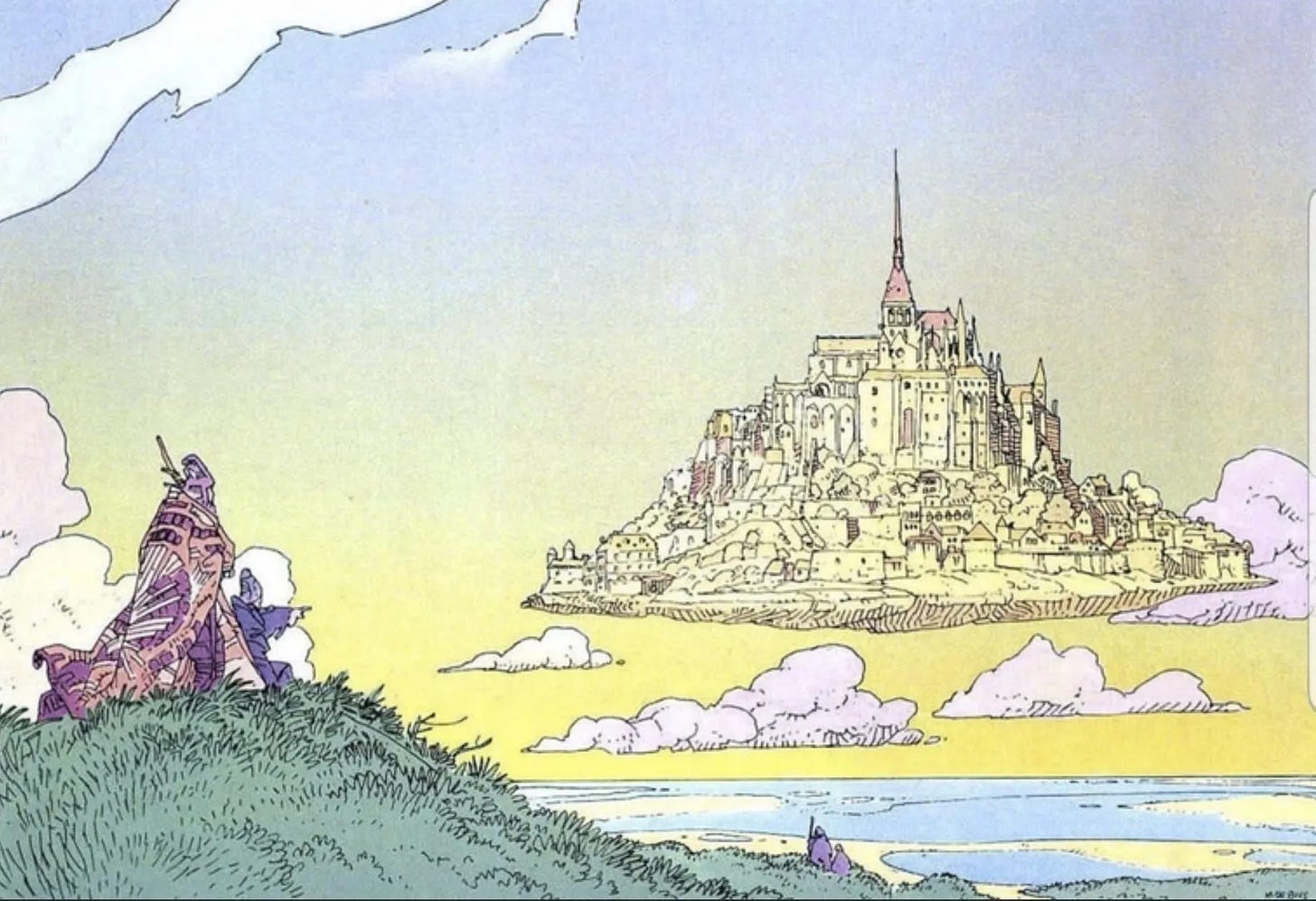

In a different recent essay, I wrote that we should believe in fairies, because belief shapes perception, and perception shapes what we are willing to try. The futures we inhabit are downstream of what we think is plausible. Plausibility is both rational and emotional.

We need those shaping the future - that is, all of us - to remember how to care. We need the thoughtful, the sensitive, the perceptive, to re-learn how to be soft. We need to believe that something gentle and beautiful is still possible.

Seeing clearly does not have to mean suffering deeply. Sensitivity does not have to end in burnout.

There is a rational case for optimism. But more importantly, there is a deeply human one, one that asks us to stay soft enough to shape it with care.

[If this piece spoke to you, I’d love if you commented or shared it - each signal sent out helps others find their way into the noise.]

“Don’t just resist cynicism — fight it actively. Fight it in yourself, for this ungainly beast lays dormant in each of us, and counter it in those you love and engage with, by modeling its opposite... Like all forms of destruction, cynicism is infinitely easier and lazier than construction. There is nothing more difficult yet more gratifying in our society than living with sincerity and acting from a place of large-hearted, constructive, rational faith in the human spirit... This remains the most potent antidote to cynicism. Today, especially, it is an act of courage and resistance.”

-Maria Popova

https://www.warpnews.org/premium-content/kevin-kelly-the-case-for-optimism/

"Cynicism isn't wisdom, it's a lazy way to say that you've been burned

It seems, if anything, you'd be less certain after everything you ever learned"

- Nana Grizol (2010)

this spoke to me, thanks so much for this amazing article <3