sometimes the grass actually is greener

when the safe path isn’t safe

“The greatest hazard of all, losing one’s self, can occur very quietly in the world, as if it were nothing at all.” —Søren Kierkegaard

A few weeks ago, I resigned from my full-time job to take a sabbatical. My hope is to spend this time writing more deeply and giving other creative projects space (more on this soon).1

Of course, this choice is scary for many reasons, not least because the economic realities are stressful. By taking this sabbatical, I’m giving up a steady paycheck, job security, the comfort of structure. But I eventually realised I no longer wanted to keep making the same trade-offs at my previous job. It turns out all paths require sacrifice, some more visible than others. The real question isn’t whether you sacrifice, but what. At some point, the greater risk is the slow erosion of what you never realised you were giving up.

(Disclaimer: I don’t mean to romanticise giving up stability. Economic precarity is real, and for many people staying in a job for security is valid and necessary. My reflections here are about the subtler sacrifices we sometimes overlook when stability turns into inertia.)

One essay I return to often is Henrik Karlsson’s Don’t Sacrifice the Wrong Thing, which argues for becoming acutely aware of the sacrifices you’re making in life, and making sure they’re the right ones. Everything comes with opportunity costs, though some remain invisible until you bump into them:

You don’t have to do things others do, or have things they have, at the expense of the deeper things you want. You really don’t. Almost everything is an option. You have full permission to ask yourself what really matters to you—whatever that is—and then optimize for that in all hard tradeoffs of life. You’re going to have to make some sacrifices anyway. Might as well not sacrifice the wrong thing.

I’ve seen what the wrong sacrifices can feel like. My first corporate job out of university was, at times, so consuming that I briefly couldn’t imagine doing anything else. Passions I’d held before seemed to vanish once I entered the company. It wasn’t even the long hours so much as how the job drained my capacity to imagine alternatives. For a while, I genuinely forgot a world outside existed. That forgetting is its own kind of sacrifice: the narrowing of your imaginative horizon, as if the sky had slowly lowered itself a little each day until you could no longer remember its original height.

I’ve also been thinking about how we frame risk. People often label themselves “risk-takers” or “risk-averse,” as if it’s fixed. At my old job, I noticed myself growing more risk-averse, conditioned by a culture of always choosing the safe option. Quitting can look risky, and often it genuinely is, but what’s less acknowledged is how staying carries risks of its own, costs that accumulate quietly.

This sabbatical is my way of reframing risk. When I look honestly, my worst-case scenario is I could move back in with my parents or take another corporate job. In other words, survivable. I also hold financial privilege (partly through the support of generous paid subscribers here), which makes this possible, something I don’t take lightly. The real gamble isn’t whether I’ll scrape by, but whether I’ll give myself the chance to live a fuller life instead of defaulting to the safer-seeming path.

a lukewarm life

That brought me to another question: what happens when we accept those “safer” paths for too long? Some people reach rupture, where the body or mind finally revolts against a misaligned life. A friend once told me about the morning he woke with the unbearable realisation that he was working in finance instead of pursuing his dream of filmmaking. The shock was so acute his body refused to go to work, and he ended up taking months off. On the surface it sounds dramatic, but in a way it was logical, an emotional revolt against the weight of misalignment carried for too long.

From what I’ve seen, though, a lot of people seem to never get that rupture. It seems far more common to drift in the lukewarm zone: not unhappy enough to leave, not fulfilled enough to thrive. In that state, invisible sacrifices accumulate year after year, trading possibility for predictability.

I’ve come to believe the greater danger is sometimes tolerable and lukewarm mediocrity. This is because catastrophe forces a change, but mediocrity can keep you still. You don’t quit because things are “fine”, but that haze of “fine” can subtly eat away a decade, or even a whole life.

distortions of glass and grit

When it comes to big choices, work, relationships, where to root your life, it seems people can lean toward one of two lenses: narrow or wide glass.

Through narrow glass, the world feels smaller than it really is. You convince yourself nothing better exists, so you cling tightly to what you have. Possibility space shrinks until other lives fade from view. You see it in the friend who stays in a lukewarm relationship because “this is as good as it gets,” or the colleague who feels drained by their job but can’t imagine leaving. To be clear, there are often good reasons for this. Financial precarity is real, and security itself is a form of dignity. Wanting stability is understandable and often necessary. My point isn’t to romanticise walking away, but I do think sometimes stability can shade into stagnation, when “at least it’s safe” becomes an excuse never to look beyond.

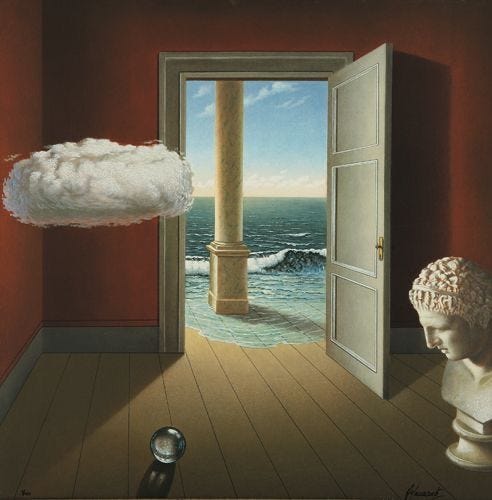

Through wide glass, the world feels overflowing with options. Every patch of grass outside looks greener, every unopened door a possible salvation. It can feel like restless freedom, the endless swipe on a dating app, the job-board scroll, the conviction that the perfect option is out there somewhere. But that promise can also make the imperfect thing in front of you feel disposable.

Both lenses distort reality. Narrow glass contracts until nothing else exists. Wide glass expands until nothing feels enough. The challenge is remembering that the distortion is in the glass we’re peering through, not the ground itself.

Once the glass is set down, another question emerges: how do we stay? Because even if we choose well, no life or relationship is endlessly green and all choices come with friction. Here is where virtues like commitment matter. Many good things only grow on the far side of long-term dedication. Nietzsche called this amor fati, the embrace of difficulty as part of the whole.

But loyalty, taken too far, can become inertia. “No job is perfect” or “every relationship has flaws” can be words of wisdom, or a way of making mediocrity feel noble. It seems the line between grit and stagnation can be thinner than we like to admit. Perhaps the real work is learning to notice when commitment deepens us, and when it has tipped into a liability.

deep roots and open horizons

One way I’ve felt these glasses most vividly is when thinking about moving cities. From when I first visited at 15, New York has called to me, a hum of neon and alive possibility, nights that end in side-street galleries at 2am, the warmth of a cookie eaten on the subway home. The city hums at a throttling voltage tuned to some hidden part of me.

Yet I deeply love the life I have built in Sydney. My days here are threaded with the rituals of friendship: shared meals, impromptu swims, my writing and essay clubs. The soil feels rich and the seedbed blooming, because of the community I’ve been lucky to nurture.

That’s the tension: staying deepens the roots that already exist, leaving opens the door to what doesn’t yet. From inside the greenhouse of habit, it’s impossible to know which risk is greater. Your glass might tint the view toward loyalty, so your ‘Sydney’ looks like the only fertile ground you’ll ever find. Or it might tint toward impatience, so New York glows impossibly green, brighter than it could ever be up close.

In truth, both views are distortions. Cities, like jobs and relationships, are dynamic systems; they bloom and wither depending on how you live inside them. The danger is mistaking the glass for the ground, forgetting that what looks barren might bloom with care, and what looks radiant might wilt when transplanted.

the grass is sometimes greener, but only if you walk

I’ve learned that sometimes the hardest part is simply believing there’s any other grass at all. Stay long enough in one place and your sense of possibility weakens. You stop asking what could be better and start asking what could be worse. That’s how invisible sacrifices accumulate, almost imperceptibly, until a decade or even a life has slipped by.

Yet, when you do step, the other side really can be more dazzling than you ever dreamed: grass that hums with colour, whole landscapes of possibility you couldn’t see from behind the glass. Other times, the leap may not deliver what you hoped, and the grass is indeed greyer. But either way, the act of stepping always changes you. It widens your horizon, restores your capacity to imagine, reminds you there are other fields beyond the one you’ve been standing in.

Here are some related reflection prompts I’ve been pondering:

Are you more prone to narrow glass or wide glass?

Which feels riskier to you right now - staying where you are, or stepping across the fence?

What sacrifices are you making without noticing, if any?

If you stepped outside your greenhouse for a moment, what might you see?

If you’d like to support my writing, I’ve set up a Buy Me a Coffee for one-off or recurring contributions. Your support means a lot and helps me keep making work like this. 💌

Other ways to support are just as meaningful: subscribing or pledging to my Substack, leaving a comment, or sharing this with someone you think would enjoy it. Each small signal helps others find their way into the noise.

I’m deeply grateful to those of you who read and support this blog; your support has made this leap feel less like stepping into the abyss and more like being caught by a soft net.

As someone who’s moved a ton and made a large amount of changes in the last decade and finally found a place to stay for a while, I love how you portray both staying and leaving in this essay. This was such great food for thought! Thank you for the perspective

“Lacking the capacity to imagine alternatives” feels like the whole point of this machine, and more and more of us are unplugging and finding ways to reclaim and cultivate our capacity for imagination