there’s always a door

on false dichotomies, constructed perception, and the doors we forget to see

“We don't see things as they are, we see them as we are.” —Anaïs Nin

Do you want to sit on the grass or at the table?

At my writing group yesterday, I asked whether we wanted to set up on the table or on the grass. Then I caught myself: why not both? We could start at the table and move to the grass, or split between them. My question had assumed a constraint that didn’t exist.

There are so many times we project false dichotomies in this life. Do you want to be a mother or a writer? Do you want a coffee or a croissant? Do you want to be ambitious or at peace?

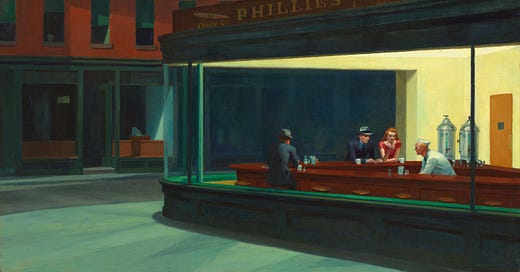

I was talking about this with M and she brought up Edward Hopper’s Nighthawks, the iconic painting of people in a bar late at night, famously without a visible door. Where is the exit? Are they trapped? Of course, the door is probably there, just outside the frame. But when you're inside the painting, it's easy to forget that. You stop looking for the exit, because you assume there isn't one.

Which raises the real question: where’s the door?

The Frame is the Trap

The constraints we live by often aren’t real. They’re inherited, projected, or simply unexamined. But not all constraints are harmful - some serve a purpose. In a world of overwhelming possibility, constraints can create clarity. They can sharpen focus, foster discipline, and offer scaffolding when we’re building something new. A frame can help us notice what matters, just as much as it can limit what we see.

But the problem is this: the frame you use shapes the questions you ask, the choices you think you have, and the kind of person you believe you’re allowed to be. Most are cages posing as context, inherited templates we didn’t realise we were following. The most dangerous ideas can be not the ones being argued, but the ones assumed.

Photography is a perfect metaphor, because the frame is never the full scene. What we focus on becomes the story, and what we ignore disappears. The crop defines what’s real. As Susan Sontag says in On Photography, to photograph is to frame, and to frame is to exclude.

Philosophers have (of course) long intuited this truth. Wittgenstein wrote, “The limits of my language mean the limits of my world.” Heidegger described us as “thrown” into structures we didn’t choose. Neuroscience agrees: through predictive processing, our brains construct reality based on past experience, constantly guessing at what’s out there and adjusting only when forced. What we see is often what we expect to see, rather than what actually is (the question of what actually is will have to be for another time).

Constructivist thinkers like Robert Anton Wilson and Timothy Leary called these ‘reality tunnels’, the subjective lenses we move through life with. Leary argued these tunnels are usually invisible, and we confuse our interpretation with reality itself. They suggest we can become aware of our filters, hold them lightly, and peek into others’ tunnels. In psychotherapy, this looks like challenging a client’s framing of a problem, noticing it as a misguided, harmful habit of interpretation, rather than fundamentally broken pathology. Epictetus explain: “Man is not disturbed by things, but by the views he takes of them.”

It’s one thing to understand this intellectually, but it’s another to meet someone who lives entirely outside your reality tunnel, and in doing so, stretches the edges of what you thought was possible.

One person I met who did that for me was A, who I met in an airbnb in Norway last summer and quietly expanded my sense of what’s possible. She spends most of the year in Berlin, immersed in art and city life, and her summers guiding cycling tours through the Norwegian wilderness. She lives two lives, two rhythms, refusing to narrow herself down to one. Most possibilities live outside the crop.

I’m reminded of this again whenever I read about people from the Romantic period - Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman - and am struck by how alien and free their lives seem. Emerson wandered the wilderness of upstate New York and came back with revelations about nature and God. Reading about them reminds me: we’re all on our own timelines, and life can be anything. We don’t have to keep playing someone else’s game.

It’s like that old taco ad where the girl is asked if she wants hard or soft shell tacos. She pauses and says, “Why not both?” Then they lift her on their shoulders like a genius. Be that girl.

For a long time, I couldn’t see this in the context of my own life. My job consumed me and became the only imaginable reality, shaping my routines, my language, my identity. But the day I left, I saw the door again and the rest of the world open there. It had actually always been there, just slightly out of view, faraway enough that I couldn’t quite make out the edges of possibility.

Constructed Perception: Question Your Maps

We’re all playing games, even when we don’t realise it, whether they be social games, professional games, status games, identity games. Most come with invisible rules.

The challenge is we start optimising for what our environments reward: praise, promotions, proximity to power (good ol’ incentive systems back at it again). Slowly, the game shapes us. We think we’re choosing, but often we’re just adapting. You could say we’re inside a trance.

James Carse defines at least two kinds of games, finite and infinite. Finite games are played to win. Infinite games are played to keep playing.

The systems we inhabit, including our jobs, friend groups, platforms, are all games. I think it can be a worthwhile exercise to pay attention to what they celebrate and what kind of person they reward you for being. And then ask: is that who you want to become? Lest you wake up one day, realising the incentive systems of some game turned you into someone you don’t like nor respect.

This is where it can be helpful to imagine the person you want to be, and work backwards. What values would that person live by? What choices would they make? From there, you can begin to build your own map, one that reflects your direction, not just your conditioning. Because sometimes, even the wrong map can get us somewhere, but a conscious one gets us there on purpose.

There’s a Miroslav Holub poem about the lost soldiers in the Alps who survive by following a map, only to later realise it was a map of the Pyrenees. The wrong map saved them, because it gave them the structure and confidence to act. Our internal maps don’t need to be accurate, but we should remember the map is not the territory.

We create mental maps of who we are, and what is possible. But those maps are stitched together from past guesses, which means they’re by definition always incomplete and the actual territory is far wilder.

These false dichotomies and maps limit ourselves. Am I soft or strong? Serious or playful? Artist or professional? The truth is: we contain multitudes. (Yes, everything on this blog comes back to that). We can be loud and quiet, precise and playful, restless and grounded. We can set up on the table and the grass. We can be the girl from the taco ad.

The Language of Possibility

I’ve recently been learning about the cultural movement of metamodernism, which helped me better understand what I’ve been circling around in this piece. Metamodernism is, in many ways, a response to postmodernism. Postmodernism taught us to be skeptical of all meaning, to deconstruct identities and truths, to view everything as relative. It shows us that perception is constructed, that language shapes reality, that there are always multiple perspectives.

But metamodernism asks: what do we do now, knowing that? It embraces both irony and sincerity, both skepticism and hope, acknowledging the absurdity and constructedness of things, then choosing to build anyway. It allows for earnestness with self-awareness, like choosing your frame while knowing it's a frame.

This is the oscillation I feel throughout my life - between idealism and realism, structure and freedom, faith and detachment. Metamodernism gives language to that and allows you to live well within the contradictions we all exist within. You see it everywhere once you know to look - in art, literature, even pop culture. Everything Everywhere All At Once is a beautiful example: chaotic, absurd, fragmented, and yet deeply sincere and emotionally resonant. It skillfully swings between nihilism and meaning-making, and somehow lands in both. BoJack Horseman lives in that same space between existential dread and fragile hope, equal parts satire and soul-searching.

To me, this is the path forward: playful construction after critical deconstruction. Believing in better maps, even when you know the territory is unknowable. Looking for the door, even when you suspect the building might be made of smoke.

You can just do things

There’s a meme-turned-mantra that circulates online: you can just do things. It sounds trite until you realise how radical it is. You really can just do things. You can become a vegan tomorrow, or maybe even a sculptor. You can move to Portugal and open a wine bar. Nobody is stopping you, except the stories you’ve internalised about what’s allowed for you.

But those stories about imagination, as much as they are about action. And imagination, too, can shrink. Depression is sometimes described as the death of imagination: the future flattens, possibility disappears. You stop being able to picture other paths, other selves. That’s why language matters, because the door you don’t believe in doesn’t get opened.

We live inside maps of meaning, models of the world, inner and outer, but it can be helpful to remember they are always approximations, flawed instruments trying to chart a dynamic and unknowable landscape. The maps aren’t necessarily wrong, but it’s worth reminding ourselves often that they’re incomplete. We must continually re-map.

So: question your frames. Check your maps. Look for the door, even if you can’t yet see it.

And remember: you can always do both.

The full poem referenced above, in case you’re interested:

“The young lieutenant of a small Hungarian detachment in the Alps sent a reconnaissance unit out onto the icy wasteland. It began to snow immediately for two days and the unit did not return. The lieutenant suffered:he had dispatched his own people to death.

But the third day the unit came back. Where had they been? How had they made their way?Yes, they said, we considered ourselves lost and waited for the end. And then one of us found a map in his pocket. That calmed us down. We pitched camp, lasted out the snowstorm and then with the map we discovered our bearings. And here we are.

The lieutenant borrowed this remarkable map and had a good look at it. It was not a map of the Alps, but of the Pyrenees

Miroslav Holub. TLS, Feb 4, ’77

Philosophical metamodernism is terrifying yet comforting, artistic metamodernism is a beautiful kaleidascope, but political metamodernism hints to me at options for a flourishing future of humanity.

I'm struggling with the concept of "the map is not the territory". A few theorists have written about this, especially Deleuze and Guittari in their twin concepts of deterritorialisation/reterritorialisation. You reminded me that this is a gap in my own knowledge I want to explore and learn more of.

Dualism is such a beautiful concept isn't it!

omfg yessssssssss

it's so hard to put it into words, but when all these framings start dissolving, everything just feels so much better

theres this zen story where a student is asked if a dog has buddha-nature, and the master just says, “mu”

It means something like "emptyness" but I read someone translating it as "un-ask the question", as in the question itself has a framing that makes any answer not complete

same as the "what sound does a single hand makes when both hands clap?" meditation

you'd LOOOOOOVE keiji nishitani's work